The Ka'ba in litterary sources - Drafts of the Ka'ba - Engravings of the Ka'ba - Representations of the Ka'ba - The Ka'ba in modern photograhpy - The Ka'ba and the prayer carpets - Pilgrimage to the Ka'ba - Muhammad and the Christian monks - Muhammad, Prophets of the Old Testament and Jesus - The Medina mosque - Representations of the Medina Mosque in prayer carpets - Several other representations of the Ka'ba

The Ka'ba is one of the large sanctuaries of mankind, very venerated by Muslims. According to Muslim tradition, it was built by Adam [1] (fig. 1), following a model given to him directly by God. Abraham [2] (fig. 2) built it with help of his brother Ismael, whom Arabs descend from, with the intention of transform it into a place of worship to the only God, and to with the intention of turning it into a pilgrimage centre. It housed the stone that fell from heaven (2.128; 3.97; 22.26-29). The second big Muslim sanctuary was located in Medina, where the Prophet's grave is preserved.

In this paper, a continuation of the previous one, other representations of the Ka'ba will be studied, and some of the Medina mosque have been added, also representations of pilgrims to Mecca, of Muhammad talking to Christian monks and the Prophet in Christ's company.

The Ka'ba in litterary sources

The paper starts with three descriptions of the Ka'ba made by Arab authors: that of Ibn Yubayr in 1183; that of Inb Battuta in 13256, that of Ali Bey at the beginning of the 19th century, and that of the Islam Encyclopaedia. The three first authors were great travellers and left good descriptions of their journeys.

Ibn Yubayr [3] was born in Játiva (Valencia) in 1145 and died in Alexandria in 1217. He visited the Ka'ba. Ybn Yubayr's description is as follows:

Ibn Battuta [4] was born in Tanger in 1304 and died in Morocco in 1377. He went to Mecca in 1326, 1327 and 1331. The description of the Ka'ba is taken from Ybn Yubayr's, but with considerable corrections and some revisions, which proves that the Sanctuary had undergone changes. The description is as follows:

Ali Bey [5] is a Spanish Muslim who visited the Ka'ba at the start of the 19th century. He describes the Ka'ba in the following terms:

The Kaaba

The Kaaba, also known as Bèït Alá or House of God, is a quadrilateral tower, with uneven sides and angles, and, as a result of this, its floor gives form to a real trapezium. Nevertheless, the huge size of the building and the black cloth covering it, make this irregularity disappear and make it look like a perfect square. I endured myself this illusion at first sight; but soon enough, I opened my eyes.

I had the biggest interest in helping to make the proportions of this temple exactly known; but how could I measure them without clashing with the precautions of the people of my religion? Only by the strength of partial measurements and approximations is how I have acheived some result; which is not of mathematical precision, but has at least an accuracy so palpable that I can take responsibility for an error of one feet in my calculation.

The building is not facing any of the four cardinal points. However, it is widely believed that the angle of the black stone is exactly facing towards E.

These are, according to my observations, the situation and the proportions of The Kaaba.

It is some sort of cubic trapeze, built or covered with similar square stones, that are not polished, of quartz rock, tourmaline or mica taken from the surrounding mountains.

The face where the door is and that forms ona of the sides of the angle of the black stone, looks towards NO 10º ½ E. Its length is 37 feet 2 inches 6 líneas, French measure.

The front, that forms the other side of the black stone’s angle, looks towards SE 15º S. Its length is 31 feet 7 inches.

The opposite side of the door is in front of SO 10 ½ E and its length is 38 feet 4 inches 6 lines.

The forth face of the side of Ismail’s stones looks towards NO 17º ½ N and is 29 feet long.

The height of the Kaaba is 34 feet 4 inches.

The door rises 6 feet above the exterior plan, 8 feet high, and 4 feet 2 inches wide: it is 6 feet away from the angle of the black stone. It has two golden and silver bronze leaves that are closed with an enormous silver chain.

The skirting board that surronds the Kaaba is made of marble and its heighth is 20 inches, and 10 inches outlet. Surrounding said skirting board there is a large number of bronza rings, fixed in the marble, on which the lower part of the huge black cloth is hanged up.

The black stone, called Hajera el Asauad or ancestral stone, is 42 inches above the exterior plan and garnished around by a huge one feet wide sheet of plate. The part of the stone thar the sheet leaves uncovered above the angle almost forms a 6 inches high semicircle, 8 inches 6 lines of diameter on its base.

We think that this miraculous stone is a transparent hyacinth brought to Abraham from heaven by angel Gabriel as a pledge of divinity, and that having been touched by an impure woman, it turned black and opaque.

Mineralogicaly speaking, its a piece of vulcanic basalt, sewn around its circumference with little tips of glass, like little straws and rhombuses of red tile feldspar on a very raised black background, as if of velvet or carbon, with the exception of one of the muscles or bumps which has something red.

The kisses and constant touches of the faithful have unevenly worn out the stone surface, so that it has acquired a musculous appearance. It has about fifteen muscles and one big hole.

Comparing the stone borders, covered and protected with the silver sheet, with the uncovered part, I have found out that this one was worn out on the surface by about twelve lines thick by the touches, from what can be inferred that, if the surface of the stone was even and united at the time of the Prophet, it has lost one line each century.

The inferior part of the Kaaba only includes a room elevated above the exterior plan, just like the door.

Two columns with less than a two feet diameter situated in the middle of the room, support the ceiling, which shape I can not point out from inside, because it is hidden by a magnificent hanged out cloth, which also coveres the walls and columns from the top until five inches above the floor.

Said cloth is of pink silk, sewn with silver flowers woven and covered with another white cloth. Each new sultan of Constantinople is obliged to send one when at the time of his advent to throne, and only then is it changed.

As the columns began to be mistreated on the lower part that is not covered by the rich cloth, they have been covered with wooden bars one to two inches wide, placed perpendicular one next to the other, and fastened with golden bronze nails.

The lower part of the walls, that has also been left uncovered, is inlayed with beautiful marble sheets, some plain, some with flowers or arabesques in relief, and others with inscriptions.

The floor is also pavimented with lovely marbles. A bar crosses from one column to the other at about seven or eight feet high, and a second bar goes from each column to the wall. They pretend to be silver. Countless silver lamps are suspended from them, grouped one above the other.

In the northern corner of the room is the ladder to get to the ceiling. It is covered by a partition wall and the door is closed.

The ceiling, flat on the upper side, has a very huge canal on the side looking NW, where the waters come out to the space surrounded by the stones of Ismail. Its said they are golden; to me, nevertheless, they looked to be golden bronze.

It has already been said that the House of God is completely covered on the outside by a huge black cloth, called Tob el Kaaba, or Shirt of the Kaaba, suspended to the ceiling and held on the lower side with cords corresponding to the bronze rings placed around the skirting board.

A new cloth is brought each year from Cairo. From there is also sent the wonderful curtain, all embroided in gold and silver, destined to cover the door.

At two thirds height, the Tob el Kaaba has a two feet wide girdle, embroided in gold, with inscriptions that are repeated on all four sides: it is called El Hazem or the waist.

At two thirds height, the Tob el Kaaba has a two feet wide girdle, embroided in gold, with inscriptions that are repeated on all four sides: it is called El Hazem or the waist.

The new tob is placed every year on Easter Day; but at the beginning, it is not completely spread like the old one. They lift the cloth froming pavillions and the door curtain is put in perspective and suspended high from the ceiling. This use has no other purpose than to protect the tob from the pilgrim’s hands; for the same reason, the old tob is cut in the Yaharmo ceremony, so the benefit of selling it at five franks an elbow, as they do, is not lost; but the trick of the servants has reduced this measure to 14 inches 4 feet lines of Paris, as I convinced myself. Nowadays there are few pilgrims who buy; so every year there is something left and soon enough there will be a considerable deposit, since said cloth can not serve other purposes because of the sacred inscriptions on it. The girdle and the door curtain belong by right to the sharif sultan, except when the first Easter day falls on a Friday; because then, it is sent to the sultan of Constantinople, whom each year is also sent water from the well of Zemzem.

I have grounds to belive that the Ka’aba formerly had another door on the opposite side to the present one, exactly facing each other; at least, that is what the outer surface of the wall predicts. It also seems that that door was similar to the one existing.

It has already been seen that, in front of the NW side of the Ka’aba, there is some kind of parapet of around five feet high and three feet thick called El Hayar Ismail or the stones of Ismail. This parapet includes a hendecagon-shaped space, almost semi-circular, pavimented with beuatiful marbles, where some infinitely beautiful green squares make out. On this side, the skirting board of the Ka’aba is cut in steps as under the door, and the rest of the circumference by an oblique surface that forms an inclined draft. In between the parapet of Ismail and the body of the Ka’aba there is a void of about six feet more or less that gives way on both sides. It is believes that Ismail or Ismael was buried in this precinct.

Although the room and the door of the Ka’aba are raised, as we have just seen, above the dratft of the patio of the temple, if the topography of that place is taken into account, it is easily noted that in the early times this hall and the door were at ground level.

Although the room and the door of the Ka’aba are raised, as we have just seen, above the dratft of the patio of the temple, if the topography of that place is taken into account, it is easily noted that in the early times this hall and the door were at ground level.

In the temple of Mecca, the Ka’aba is the only existing old building existing; everything else has been added later.

The temple is located almost in the middle of the city, which is built in a valley pretty sloped from N to S.

The temple is located almost in the middle of the city, which is built in a valley pretty sloped from N to S.

It is can be easily realized that when the huge patio and the other parts of the building were tried to be formed, instead of going deeper on one side and embank on the other with the goal of leveling the ground and thus have a medium level, they dug everywhere; so, in order to get inside the temple from any given side, it is necessary to come down a few steps, because the paviment is many feet lower than the general draft of the ground and the streets around it; even the floor immediately enclosing the Ka’aba forming an oval surfaced paved in marble, on which the pilgrims go around in the House of God, is the lowest part of the temple.

Assuming the ground around the Ka’aba raised to its natural height up to the level of the streets surrounding the temple, as it was when this old building found itself isolated, it has to be admitted that the height of the room and the door belong exactly to the general level and, therefore, there was no need then for a staircase to come in.

It is true that in that case it would have been precise to assume that the black stone was in a different place than where it is nowadays, because it is seen almost two feet under the door level. Someone unfaithful would say that it may not have existed, or that it was under the earth: as far I am concerned, I would not be able to form such an idea of that beautiful garment of divinity.

It is true that in that case it would have been precise to assume that the black stone was in a different place than where it is nowadays, because it is seen almost two feet under the door level. Someone unfaithful would say that it may not have existed, or that it was under the earth: as far I am concerned, I would not be able to form such an idea of that beautiful garment of divinity.

The wooden stair that is place in front of the door of the Ka’aba to go up on the days when it is opened to the public is set up on six bronze rollers with handrails on both sides and ten steps of about eigh feet wide.

Next to the door of the Ka’aba, on the opposite side of the black stone, there is a little one foot deep pit, paved in marble, on which particular merit is gained by praying.

Next to the door of the Ka’aba, on the opposite side of the black stone, there is a little one foot deep pit, paved in marble, on which particular merit is gained by praying.

Makàm Ibrahim

Makàm Ibrahim, or place of Abraham, forms some kind of a parallelogramic dining room on the opposite side and 34 and a half feet away from the central point of the wall, where there is the door to the Kaaba. This parallelogram, which is 12 feet and 9 inches long, and 7 feet and 8 inches wide, faces the Kaaba on its narrower side. The ceiling is held up by six pillars not much higher than a man.

Half of the parallelogram, on the side of the House of God, is surrounded by beautiful bronze bars that embrace four pillars, and its door is always closed with a huge silver chain.

These bars contain some kind of sarcophagus, covered by a magnificent black cloth embroided in gold and silver, with thick golden tassels, which is nothing else than a huge stone that served Abraham as a footstool to build the Kaaba. It is said that this footstool became higher as the building works made progress, so that it could help make the efforts easier, and at the same time, the stones, which came miraculously already square from the earth at the place where the footstool is presently to be found, passed from the hands of Ismail to those of his father. For this reason, when walking around the House of God, one also goes to the place of Abraham and a prayer is held as ordered by rite. The place that contains the bar is crowned by an elegant little dome.

These bars contain some kind of sarcophagus, covered by a magnificent black cloth embroided in gold and silver, with thick golden tassels, which is nothing else than a huge stone that served Abraham as a footstool to build the Kaaba. It is said that this footstool became higher as the building works made progress, so that it could help make the efforts easier, and at the same time, the stones, which came miraculously already square from the earth at the place where the footstool is presently to be found, passed from the hands of Ismail to those of his father. For this reason, when walking around the House of God, one also goes to the place of Abraham and a prayer is held as ordered by rite. The place that contains the bar is crowned by an elegant little dome.

Bir Zemzem

Bir Zemzen, or Zemzen well, is located 51 and a half feet towards E. 10º N of the black stone.

It has a diameter of about 7 feet and 8 inches, and is 56 feet deep down to the water surface.The parapeth is made of beautiful white marble and is 5 feet high.

It has a diameter of about 7 feet and 8 inches, and is 56 feet deep down to the water surface.The parapeth is made of beautiful white marble and is 5 feet high.

To take out the water, it is necessary to climb the parapet, and on its interior side, there is an iron coping with a copper plate to lean a foot, and, as there are no steps to climb, one has to jump first to an adjoining window, and then climb to the parapet. All these difficulties have no other purpose than to hinder pilgrims to take out the water for themselves and to not deprive the well servants off the incentives attached to his occupation. Three bronze pulleys with hemp ropes and leather at the end of the ropes serve to take out the water, which is heavy and brackish, albeit very clear. In spite of the depth of the well and the heat of the climate, when it comes out of the well, it is warmer than the environment and looks tepid, which proves there exists a particular cause for this vehement heat that at the bottom.

I have four bottles of that water, which I took out myself and closed as soon as it came out of the well, with all the precautions that chemistry demands, so that one day it would be able to do an analysis. One hour after putting it into bottles, which were perfectly closed with emery and glass caps and immediately sealed, the whole interior surface was covered with little air bubbles, very subtle and simmilar to a pinhead. A little shaking of the bottle made them go up to the upper surface, where they met together in one bubble as thick as chickpea; it was, without a doubt, some kind of gas that was enough to give off the sole temperature difference.

Nobody ignores that said well was miraculously opened by the angel of the Lord in favour of Agar, just as he was going to die of thirst in the desert with his son Ismail, after she was sent off the house of Abraham.

Nobody ignores that said well was miraculously opened by the angel of the Lord in favour of Agar, just as he was going to die of thirst in the desert with his son Ismail, after she was sent off the house of Abraham.

A house has been built around the well, composed of the part where it is found, another little one that serves as a storage room for the pitchers and is divided in two parts: one destined for prayer for the schaffi rite sectarians, the crown is an elegant dome supported by eight pillars, the other one contains two big horizontal marble quadrants, destined to mark the prayer hours.

The monkis, that is, the person in charge of noticing in the quadrants the hour of prayer, starts shouting the summoning formula to Makam Schaffi; right then, seven muezzins or shouters repeat the formula from the top of the seven minarettes. Another door has been practised in the staircase to get up to the terrace, indepedent of those in the well and in the pitcher storage room. Therefore, this little building counts three doors.

The monkis, that is, the person in charge of noticing in the quadrants the hour of prayer, starts shouting the summoning formula to Makam Schaffi; right then, seven muezzins or shouters repeat the formula from the top of the seven minarettes. Another door has been practised in the staircase to get up to the terrace, indepedent of those in the well and in the pitcher storage room. Therefore, this little building counts three doors.

The room where the well is 17 feet and 3 inches square, has three windows towards W on the side of the Kaaba, another three ones towards N, the door and two windows towards E. It is entirely covered and paved in beautiful marble. On the souther side, three niches can be seen in the wall that separates the room from the pitcher storage room. The exterior parte is decorated by a little facade of lovely white marble.

The number of pitchers in the well is immense: not only do they occupy the little room that I have just spoken about, but also the two neighbouring cobas and several storage rooms located around the temple yard.

The number of pitchers in the well is immense: not only do they occupy the little room that I have just spoken about, but also the two neighbouring cobas and several storage rooms located around the temple yard.

The shape of these pitchers is strange: they have a long neck or cylindric throat, with a belly as long as the neck, and they end in a cone or point on the inferior side, so they can not be upright if not leaned on the wall. Their total length, as they are all equal, is fifteen inches, their biggest diameter is seven inches and six lines. They are made of unglazed soil and are so porous that they are constantly filtering water, but they also cool it in a moment.

As soon as a distinguished pilgrim arrives in Mecca, his name is written down in the great book of the Zemzem well boss; at the same time, he entrusts a servant to provide the pilgrim with water and to take it to his home, something that is carried out punctually. The pitchers have the name of the pilgrim written in black wax, and, furthermore, some mystic inscription.

Outside the pitchers supplied to the pilgrims, the Zemzem water carriers are constantly walking around the temple in order to sell or distribute it. Usually late in the afternoon a large number of large and narrow rush mats are spread out in the patio of the temple, and in front of each one of them a line of half-filled pitchers are obliquely placed. The people who come to to sit down on the rush mat have each one pitcher in front of them; this is something very pleasant in a warm country that attracts a lot of people to the temple, even before mogareb time, and it is a time of reunion, during which to pray or to have an entertaining conversation until the time of prayer.

Outside the pitchers supplied to the pilgrims, the Zemzem water carriers are constantly walking around the temple in order to sell or distribute it. Usually late in the afternoon a large number of large and narrow rush mats are spread out in the patio of the temple, and in front of each one of them a line of half-filled pitchers are obliquely placed. The people who come to to sit down on the rush mat have each one pitcher in front of them; this is something very pleasant in a warm country that attracts a lot of people to the temple, even before mogareb time, and it is a time of reunion, during which to pray or to have an entertaining conversation until the time of prayer.

The Zemzem servants carry the pitcher on their left shoulder, covered with some kind of dry grass that prevents that dust or insects get inside, but does not hinder water coming out, if they want to pour it without taking it off. In their right hand thay carry a little well tinned cup, in which they present the water, to those who ask for it, as well as those who do not.

Beb-es-Selem

Beb-es-Selem, or the Greeting door, is an isolated arch, shaped like a triumphant arch, situated 17 feet away from Makam Ibrahim, almost in front of this monument, on the opposite side of the Kaaba.

This arch, built with ashlar stone and ending with a point, is 15 feet and 6 inches high, and 19 feet and 6 inches wide, including the thickness of the arch bases.

I already said it is a good omen and a special pledge to walk under this arch the first time one arrives to turn seven times around the Kaaba.

This arch, built with ashlar stone and ending with a point, is 15 feet and 6 inches high, and 19 feet and 6 inches wide, including the thickness of the arch bases.

I already said it is a good omen and a special pledge to walk under this arch the first time one arrives to turn seven times around the Kaaba.

The minbar

The minbar, or rostrum for Friday’s preacher, is next to Makam Ibrahim, at a distance of 14 feet in front of the N angle of the Kaaba.

This rostrum, made of the most beautiful white marble, is the best finished and beautiful piece of art in the temple. It is built in a staircase shape and ends with a square, upon which a lovely octagonal piramidal dome rises, which looked to me of golden bronze; holding it up are four little columns, united with little arches, that have something of the corinthian order, but in reality do not belong to none of the five orders of architecture.

The exterior sides, the balustrade, the door and the base, are exquisitely crafted. The stair is closed by a bronze bar. The stair might be about three feet wide.

This rostrum, made of the most beautiful white marble, is the best finished and beautiful piece of art in the temple. It is built in a staircase shape and ends with a square, upon which a lovely octagonal piramidal dome rises, which looked to me of golden bronze; holding it up are four little columns, united with little arches, that have something of the corinthian order, but in reality do not belong to none of the five orders of architecture.

The exterior sides, the balustrade, the door and the base, are exquisitely crafted. The stair is closed by a bronze bar. The stair might be about three feet wide.

Here, as is the case in other mosques, the Imam does not go up to the end of the rostrum to preach the sermon, but he stays on the penultimate step, with his back turned towards the Kaaba.

A special circumstance that I have not seen anywhere else is that the Imam wears a specifically assigned costume to preach the sermon and for the Friday prayer, which is a huge caftan of light cloth made with white wool, and an equally light and clear shawl that covers his head, and after wrapping it once around the neck, it gets ready so that both ends end up hanging down the front.

The Kaaba and the stones of Ismail, placed almost in the middle of the temple, take up the centre of an oval surface or irregular ellipsis, that forms a 39 feet wide area around this building, on which the pilgrims walk when they turn around the Kaaba. The surface, paved with beautiful marble, is located, as we said, on the lowest plan of the temple.

The temple is surrounded by another 31 feet wide irregular eliptic surface, one foot higher than the previous one, and paved with ordinary quartz ashlar stones.

Upon the stands that form the limit between both planes, a row of thirty one slim columns or bronze pillars rises, with another stone pillar on each end.

These pillars are about seven feet and six inches from the lower end to the upper part of a little capital, where several iron bars lean on that go from one pillar to another, and from which a large number of lamps are hanging around the House of God. The capital has a golden decoration, and is rounded off by a half moon. The cylindric pillars are hardly three inches in diameter. Some kind of cord is evident at half of their height. Each pillar rests upon a cylindric stone of one foot height and diameter.

The lamps have, more or less, ballon-shaped, of very thick and not very transparent green glass, and are arranged with no order nor symmetry in the pillar intervals: they get lit up every night.

The prayer places for the three remaining orthodox muslim rites can be seen on the exterior plane, and are called Makam Hanèffi, Makam Máleki and Makam Hanel.

The Makam Hanèffi, located facing the stones of Ismail, serves the turkish rite. It consists of some kind of isolated gallery, supported by twelve pilasters on three arches at the front and two arches width. Its plan is a parallelogram where each side is 29 feet and 3 inches, and the little ones 15 feet and a half. The height of the pilasters barely exceeds the ordinary size of a man.

On top there is another gallery of identical dimensions: the stairs to get up on the E angle.

Makam Malèki, located facing the Kaaba , on the opposite side of the door, is a huge square of four pilasters that holds the ceiling: it is about 11 square feet. The pilasters height is the same as the Makam Hanèffi.

The ceilings of these buildings, as well as those of Zemzem and Makam Ibrahim, are covered with lead and big flights to secure shade, and the pilasters are not so tall for the same reason.

All mentioned prayer places have up front a three feet high parapet, with some kind of niche in the half destined for the Imam; but as everythng has changed since the wahabi reform, the Hanèffi and Habeli Imams do their praying at the foot of the Kaaba, facing the door; the Schaffi Imam inside Makam Ibrahim, and the Màleki Imam is the only one who does it at his place.

The black eunuchs, housekeepers and guards of the Kaaba, sit down in Makam Hanbeli, where they have some furnitures and carpets. At the time of public prayer, the singers, who are also the black eunuchs, form the chorus in the upper gallery of Makam Hanèffi.

To get inside the paved area where these buildings are, it has to be done through six roads, equally paved with quartz slabs, that leave from huge galleries facing the doors of Selém, Nebi, Sàffa, Udaa, Ibrahim and Aàmra. The paved roads, about ten feet six inches wide and rising one foot above the general plane of the patio, are in touch with smaller ones, leading to several places of the galleries.

The rest of the patio is nothing more than rough sand and usual dwelling of more than two thousand pigeons belonging to the Shereef Sultan.

A special circumstance that I have not seen anywhere else is that the Imam wears a specifically assigned costume to preach the sermon and for the Friday prayer, which is a huge caftan of light cloth made with white wool, and an equally light and clear shawl that covers his head, and after wrapping it once around the neck, it gets ready so that both ends end up hanging down the front.

The Kaaba and the stones of Ismail, placed almost in the middle of the temple, take up the centre of an oval surface or irregular ellipsis, that forms a 39 feet wide area around this building, on which the pilgrims walk when they turn around the Kaaba. The surface, paved with beautiful marble, is located, as we said, on the lowest plan of the temple.

The temple is surrounded by another 31 feet wide irregular eliptic surface, one foot higher than the previous one, and paved with ordinary quartz ashlar stones.

Upon the stands that form the limit between both planes, a row of thirty one slim columns or bronze pillars rises, with another stone pillar on each end.

These pillars are about seven feet and six inches from the lower end to the upper part of a little capital, where several iron bars lean on that go from one pillar to another, and from which a large number of lamps are hanging around the House of God. The capital has a golden decoration, and is rounded off by a half moon. The cylindric pillars are hardly three inches in diameter. Some kind of cord is evident at half of their height. Each pillar rests upon a cylindric stone of one foot height and diameter.

The lamps have, more or less, ballon-shaped, of very thick and not very transparent green glass, and are arranged with no order nor symmetry in the pillar intervals: they get lit up every night.

The prayer places for the three remaining orthodox muslim rites can be seen on the exterior plane, and are called Makam Hanèffi, Makam Máleki and Makam Hanel.

The Makam Hanèffi, located facing the stones of Ismail, serves the turkish rite. It consists of some kind of isolated gallery, supported by twelve pilasters on three arches at the front and two arches width. Its plan is a parallelogram where each side is 29 feet and 3 inches, and the little ones 15 feet and a half. The height of the pilasters barely exceeds the ordinary size of a man.

On top there is another gallery of identical dimensions: the stairs to get up on the E angle.

Makam Malèki, located facing the Kaaba , on the opposite side of the door, is a huge square of four pilasters that holds the ceiling: it is about 11 square feet. The pilasters height is the same as the Makam Hanèffi.

The ceilings of these buildings, as well as those of Zemzem and Makam Ibrahim, are covered with lead and big flights to secure shade, and the pilasters are not so tall for the same reason.

All mentioned prayer places have up front a three feet high parapet, with some kind of niche in the half destined for the Imam; but as everythng has changed since the wahabi reform, the Hanèffi and Habeli Imams do their praying at the foot of the Kaaba, facing the door; the Schaffi Imam inside Makam Ibrahim, and the Màleki Imam is the only one who does it at his place.

The black eunuchs, housekeepers and guards of the Kaaba, sit down in Makam Hanbeli, where they have some furnitures and carpets. At the time of public prayer, the singers, who are also the black eunuchs, form the chorus in the upper gallery of Makam Hanèffi.

To get inside the paved area where these buildings are, it has to be done through six roads, equally paved with quartz slabs, that leave from huge galleries facing the doors of Selém, Nebi, Sàffa, Udaa, Ibrahim and Aàmra. The paved roads, about ten feet six inches wide and rising one foot above the general plane of the patio, are in touch with smaller ones, leading to several places of the galleries.

The rest of the patio is nothing more than rough sand and usual dwelling of more than two thousand pigeons belonging to the Shereef Sultan.

Women and boys selling little plates of wheat for the price of one para each can be found all the while on the paved roads. The pilgrims never forget to destine some paras to buy some wheat plates for the pigeons inside the temple; which is a very pleasant reparation work in the eyes of divinity and Shereef.

In front of the Zemzem well door and not for away, one can see El Cobbataïn, or the two cobas: they are two adjoining chapels, each one of them forming an 18 feet square on the side, whose point of contact presents a diagonal angle. The shape and dimensions of both are exactly the same, and one and the other are finished off with a beautiful channeled dome. It is known that both cobas serve as a wharehouse for the Zemzem pitchers; one is also used for the pilgrims to wash and bath with the water from the well.

The area surrounding Makam Hanèffi is paved like the roads and forms kind of a fishtail towards the big gallery behind that place.

In front of the Zemzem well door and not for away, one can see El Cobbataïn, or the two cobas: they are two adjoining chapels, each one of them forming an 18 feet square on the side, whose point of contact presents a diagonal angle. The shape and dimensions of both are exactly the same, and one and the other are finished off with a beautiful channeled dome. It is known that both cobas serve as a wharehouse for the Zemzem pitchers; one is also used for the pilgrims to wash and bath with the water from the well.

The area surrounding Makam Hanèffi is paved like the roads and forms kind of a fishtail towards the big gallery behind that place.

The big patio, confined by four porches held by columns and pillars, represents a parallelogram, whose big sides in the E 34º ½ N towards W 34 ½ S direction are 536 and 9 inches long, and the small ones 350 in a N 34º ½ W towards S 34º ½ E.

The facade on each big side has thirty six at the front arches, and every one of the small ones, twenty four. These arches are slightly pointed, and are held up by grey white marble columns of different proportions, although, in general, they are approaching the dorics.

Every four arches rises a three feet diameter octogonal pilaster of ashlar stones instead of a column.

The facade on each big side has thirty six at the front arches, and every one of the small ones, twenty four. These arches are slightly pointed, and are held up by grey white marble columns of different proportions, although, in general, they are approaching the dorics.

Every four arches rises a three feet diameter octogonal pilaster of ashlar stones instead of a column.

Each side of the big galleries is made up of three naves or three arch orders, with the exception of some partial irregularities, all equally held up by columns and pillars, so more than five hundred columns and pilasters can be counted to support the galleries or temple porches.

The capitels of the columns that form the four facades of the patio are very beautiful, although they do not belong to any of the five orders in architecture; but the capitels of the columns in the interior of the galleries belong all to the Corinthian order, and many of them have been worked with utmost delicacy.

The bases of the columns are usually attic; there are others with a little attic or lowered pedestal; others with a false base, and some, by whim of an outrageous architect, have a reverse Corinthian capital.

The arches facing the patio, are crowned by a little Ionic dome; but the interiors do not have but spherical half pointed vaults.

The capitels of the columns that form the four facades of the patio are very beautiful, although they do not belong to any of the five orders in architecture; but the capitels of the columns in the interior of the galleries belong all to the Corinthian order, and many of them have been worked with utmost delicacy.

The bases of the columns are usually attic; there are others with a little attic or lowered pedestal; others with a false base, and some, by whim of an outrageous architect, have a reverse Corinthian capital.

The arches facing the patio, are crowned by a little Ionic dome; but the interiors do not have but spherical half pointed vaults.

The four sides of the patio are rounded off with stone decorations quite similar to a fleur-de-Lis.

These galleries are paved, just as the roads and the temple walls, with cut stones of quartz rock mixed with tourmaline and mica, a sort of crag that is abundant in the country.

The E temple angle is cut off and rounded to follow the line of the main street, and goes so far as to be so narrow at that point of the gallery, that there is almost no space to walk through in between the wall and the patio angular pilastre.

On the SE wing or gallery of the temple, from the Saffa door to the Zeliha door, there is a fourth row of arches, where some irregularities can be seen in its layout.

The Kaaba is not exactly located in the centre of the patio. The NE facade is 275 feet 6 inches away from its corresponding gallery; the SE side, 155 feet 6 inches; the SW side, 229 feet 3 inches; and the facade, 162 feet of the opposite side.

These galleries are paved, just as the roads and the temple walls, with cut stones of quartz rock mixed with tourmaline and mica, a sort of crag that is abundant in the country.

The E temple angle is cut off and rounded to follow the line of the main street, and goes so far as to be so narrow at that point of the gallery, that there is almost no space to walk through in between the wall and the patio angular pilastre.

On the SE wing or gallery of the temple, from the Saffa door to the Zeliha door, there is a fourth row of arches, where some irregularities can be seen in its layout.

The Kaaba is not exactly located in the centre of the patio. The NE facade is 275 feet 6 inches away from its corresponding gallery; the SE side, 155 feet 6 inches; the SW side, 229 feet 3 inches; and the facade, 162 feet of the opposite side.

On the SW of the big patio, a smaller one can be seen, also surrounded by arches, where the Ibrahim door is situated; there is also a similar one on the NE wing, and there the Kutubia and Ziada doors can be seen.

The temple has nineteen doors, with thirty-eight arches, arranged around the temple as follows, from N to E (indicating the number of arches on each door).

On the N angle: Beb-es-Selem, 3; Beb en Nebi, 2; Beb Abasi, 3; and Beb Aali, 3. On the E angle: Beb Zitun, 2; Beb Begala, 2; Beb Saffa, 5; Beb Arrahma, 2; Beb Moyahet, 1; Beb Zelina, 2; and Beb Omhani, 2. On the south angle: Beb l’Udaa, 2; Beb Ibrahim, 1; Beb El Aamara, 1. On the W angle: Beb el Aatik, 1; Beb Bastia, 1; Beb Kutubia, 1; Beb Ziada, 2; and Beb Duriba, 1.

Of all doors, only Saffa is the one that has a real decorated facade; the others are extremely simple.

The temple has nineteen doors, with thirty-eight arches, arranged around the temple as follows, from N to E (indicating the number of arches on each door).

On the N angle: Beb-es-Selem, 3; Beb en Nebi, 2; Beb Abasi, 3; and Beb Aali, 3. On the E angle: Beb Zitun, 2; Beb Begala, 2; Beb Saffa, 5; Beb Arrahma, 2; Beb Moyahet, 1; Beb Zelina, 2; and Beb Omhani, 2. On the south angle: Beb l’Udaa, 2; Beb Ibrahim, 1; Beb El Aamara, 1. On the W angle: Beb el Aatik, 1; Beb Bastia, 1; Beb Kutubia, 1; Beb Ziada, 2; and Beb Duriba, 1.

Of all doors, only Saffa is the one that has a real decorated facade; the others are extremely simple.

The temple has seven minarettes, for on the four angles, another one in between Beb Ziada and Beb Duriba, and the two last ones separated from the temple body in between the houses next to NE wing. These towers, all of them octogonal and consisting of three bodies, have all the same shape, but not the same dimensions.

On the outside, the houses conceal the temple walls, so there is no exterior facade. On some of these houses, windows facing the interior of the temple can be seen.

On the outside, the houses conceal the temple walls, so there is no exterior facade. On some of these houses, windows facing the interior of the temple can be seen.

Employees at the Temple

The Haram has its chief principal, called sheikh el Haram.

The Zemzem well also has its own chief, called sheikh Zemzem.

Forty black eunuchs carry out the domestic service of the Kaaba. They are guards and domestic employees of the House of God. Their distinction mark is a huge caftan or white cloth shirt over their ordinary dress, held by a belt, with a big white turban and, commonly, a rod or little sitck in their hands.

The Zemzem well counts a grown number of employees and guards, who are in charge of the administration of the rush mats that are spread out every afternoon over the patio floor and the temple galleries.

There are also an infinite number of employees, such as lampists, awakers, servants of Makam Ibrahim, of the little Kaaba pit, of every place of prayer for the four rites, assistants of the minarettes, servants of Saffa and Merua; and they guard their respective places where they are destined. There are also servants who keep the pilgrim sandals on every door of the temple entrance; public shouters or minaret muezzins; imams or particular muezzins for every single one of the four rites; the Cadi and its employees; the choir singers; the Monkis, or observer of the sun, who announces prayer times; the administrator and servants of Tob el Kaaba; the trustee of the Kaaba key; the Mufti; the guides etc. Almost half of Meca’s inhabitants can be considered employees or domestics of the temple, and they have no other salary than the eventual alms or donations made by pilgrims.

The Zemzem well also has its own chief, called sheikh Zemzem.

Forty black eunuchs carry out the domestic service of the Kaaba. They are guards and domestic employees of the House of God. Their distinction mark is a huge caftan or white cloth shirt over their ordinary dress, held by a belt, with a big white turban and, commonly, a rod or little sitck in their hands.

The Zemzem well counts a grown number of employees and guards, who are in charge of the administration of the rush mats that are spread out every afternoon over the patio floor and the temple galleries.

There are also an infinite number of employees, such as lampists, awakers, servants of Makam Ibrahim, of the little Kaaba pit, of every place of prayer for the four rites, assistants of the minarettes, servants of Saffa and Merua; and they guard their respective places where they are destined. There are also servants who keep the pilgrim sandals on every door of the temple entrance; public shouters or minaret muezzins; imams or particular muezzins for every single one of the four rites; the Cadi and its employees; the choir singers; the Monkis, or observer of the sun, who announces prayer times; the administrator and servants of Tob el Kaaba; the trustee of the Kaaba key; the Mufti; the guides etc. Almost half of Meca’s inhabitants can be considered employees or domestics of the temple, and they have no other salary than the eventual alms or donations made by pilgrims.

LIII. Floor of the temple of Mecca, also known as El Haram.

1. The Ka’aba, Beith Ala or House of God.

2. Two of the columns that hold the ceiling.

3. Staircase to get up to the terrace.

4. Pit that goes around the whole building.

5. Corner of the black stone.

6. Little pit.

7. The stones of Ismael.

8. Eliptic surface, tiled with marble, on which the pilgrims turn seven times around the Ka’aba.

9. Thirty one little bronze pillars and two made of stone, hold, on both sides, the iron bars from which the glass tears that light up every night are hanging.

10. Almimbar or preacher stand.

11. El Makam Ibrahim or place of Abraham.

12. The wooden staircase that is laid upon six bronze rolls to get inside the Ka’aba.

13. The Zemzem well, opened by the archangel of the Lord for Agar and Ismael.

14. Staircase that leads to the terrace, where there are several sundials destined to set the praying hour and where Makaam Schaffi is, place of prayer for followers of theis rite.

15. Makam Hambeli or place of prayer for the faithful of this rite. A black eunuch guard is always positioned at this place, whose mission is to protect the black stone.

16. Makam Maleki, or prayer hall for this rite.

17. Makam Haneffi or place to practice this Turkish rite. Above is the choir for singers.

18. Isolated arch, demonized Beb es Selem.

19. Two stalls, known as El Cobbaittin, currently used as warehouse.

Gates of the Temple

20. Beb es Selem 30. Beb Omhani

21. Beb en Nebi 31. Beb el Udaa

22. Beb el Abassí 32. Beb Ibrahim

23. Beb Aali 33. Beb el Aamara

24. Beb Litum 34. Beb el Aatik

25. Beb el Bagala 35. Beb el Bastia

26. Beb Saffa 36. Beb Kutubia

27. Beb Arrayma 37. Beb Ziada

28. Beb Moyahed 38. Beb Duriba

29. Beb Zeliha

39. Tiled paths about an inch high above the general draft of the patio, which is

covered with sand.

40. Six minarettes or towers linked to the temple, and a seventh one separated

From the building and placed in between the neighbouring houses.

(Scale in Paris feet)

1. The Ka’aba, Beith Ala or House of God.

2. Two of the columns that hold the ceiling.

3. Staircase to get up to the terrace.

4. Pit that goes around the whole building.

5. Corner of the black stone.

6. Little pit.

7. The stones of Ismael.

8. Eliptic surface, tiled with marble, on which the pilgrims turn seven times around the Ka’aba.

9. Thirty one little bronze pillars and two made of stone, hold, on both sides, the iron bars from which the glass tears that light up every night are hanging.

10. Almimbar or preacher stand.

11. El Makam Ibrahim or place of Abraham.

12. The wooden staircase that is laid upon six bronze rolls to get inside the Ka’aba.

13. The Zemzem well, opened by the archangel of the Lord for Agar and Ismael.

14. Staircase that leads to the terrace, where there are several sundials destined to set the praying hour and where Makaam Schaffi is, place of prayer for followers of theis rite.

15. Makam Hambeli or place of prayer for the faithful of this rite. A black eunuch guard is always positioned at this place, whose mission is to protect the black stone.

16. Makam Maleki, or prayer hall for this rite.

17. Makam Haneffi or place to practice this Turkish rite. Above is the choir for singers.

18. Isolated arch, demonized Beb es Selem.

19. Two stalls, known as El Cobbaittin, currently used as warehouse.

Gates of the Temple

20. Beb es Selem 30. Beb Omhani

21. Beb en Nebi 31. Beb el Udaa

22. Beb el Abassí 32. Beb Ibrahim

23. Beb Aali 33. Beb el Aamara

24. Beb Litum 34. Beb el Aatik

25. Beb el Bagala 35. Beb el Bastia

26. Beb Saffa 36. Beb Kutubia

27. Beb Arrayma 37. Beb Ziada

28. Beb Moyahed 38. Beb Duriba

29. Beb Zeliha

39. Tiled paths about an inch high above the general draft of the patio, which is

covered with sand.

40. Six minarettes or towers linked to the temple, and a seventh one separated

From the building and placed in between the neighbouring houses.

41. Two little patios. The galeries surrounding these patios are covered with little

Conical domes, held by thick octogonal stone pillars and by marble columns.LVII. 1. Main facade of the hall sheltering the Zemzem well, in the temple. The little front is made of beautiful marble.

2. View of the Zemzem well. The parapet and the room are of beautiful white marble.LVIII. 1. Bedouin barrack in the desert of Mecca.

2. Housing of the barrack.

3. Wooden stairs to get inside the Kaaba, seen from the front.

4. The same stairs seen in profile.

5. Makam Ibrahim or place of Abraham. Some kind of tomb, covered by a

magnificent embroided cloth and protected by railings. It designates the

place from which the stones used to build the Kaaba miraculously came up. Ismael received them and gave them to his father, who places them in

their place.

6. Plant and elevation of the isolated arch, known as Beb es Selem, situated

next to the Kaaba.

7. Minbar or tribune of the preacher, built with beautiful white marble.

8. Little bronze pillars that surround the Kaaba.

9. Makam Maleki or place of prayer for this rite supporters.

10. Golden lamps hanging inside the Kaaba.

11. Glass lamps hanging in between the thin bronze pillars.

12. Tip of the Kaaba key.

13. Brazier used to perfume the interior of the Kaaba.

14. Shape of the pitchers used to take the water out of the Zemzem well.

15. Shape of the capitel of many columns in the temple.

LIX. 1. Door of the temple, called Beb Saffa.

2. Palace of the Shereef Sultan of Mecca.

a. Part of the building where he lives together with his wives.

b. Part reserved for the servants and stables. Two of the doors are blocked

off.

The Encyclopedia of Islam [6] has done a description of the Ka'ba just as it is nowadays. It says:

These descriptions of the Ka'ba made by pilgrims and the one of the Islam Encyclopedia are important to understand the transformations of the Sanctuary throughout the centuries up to the present moment.

Drafts of the Ka'ba

Several very accurate drafts of the Ka'ba have been made over the centuries. We shall only pay attention to two. Aly Bey's has already been reproduced. He was a good drawer and wanted to reproduce reality, just as the Sanctuary was at the start of the 19th century. It is therefore a very valuable draft due to its accuracy.

The second one is the work of Rutter, and it is just as the sanctuary was in 1928 [7] (fig. 6).

Engravings of the Ka'ba

Some engravings of the Ka'ba have been made. One of the relatively older ones is very simple. The Scantuary is isolated. Several buildings that surround the cube can be found inside the holy precinct [8] (fig. 7). The engraving represents the Ka'ba from a bird's eye view. A miniature from the 15th century is important for its simplicity. A row that ends with five circular buildings crowned with domes can be seen at the back. Mecca is represented by only a few isolated buildings that surround the holy precinct, which takes up the engraving centre, also from a bird's eye view [9] (fig. 8). This engraving is a lithograph from the 19th century that has been reproduced lately [10] (fig. 9).

According to numerous authors, the Ka'ba did not have originally any wall around it. In the 11th century, it was visited by renowned traveller Nassir-Khosran and it already was as nowadays, in the centre of a precinct which included the Zem Zem well and the oil warehouse. Selim II set up an irregular oval shaped marble pavement in 1537, that was surrounded by 32 golden bronze columns linked with iron barrs, from which Seven lamps hung in between the columns that were lit up at sunset, the same as the ones placed above the wall build by Omar.

Mecca historian Khalib-ed-Dios and El-Azraky's Memoirs book describe the Sanctuary as a square building measuring 18 x 14. El-Azraky states the Ka'ba had no wall around it, only the coraisi's houses were surrounded.

The Ka'ba was enlarged during Omar's time, incorporating the houses in the surroundings. Omar ordered to lift a wall around the Ka'ba of a man's height, and to place lamps on it and doors to get inside the holy precinct.

A draft of the Ka'ba and its surroundings can be found in a Persian miniature from 1596 by copyist Bader i Mumirb Mahmud from Bukhasa [11].

Representations of the Ka'ba

Representations of the Ka'ba are numerous in Persian, Ottoman and Egyptian art. Only a few others are collected besides the ones collected in this paper and the previous one.

In Firdausi's Shahmana, at the end of the 15th century, it is told that Alexander the Great marched from India to Mecca to visit the Ka'ba, a visit that is represented in an illustration of this epitome. The Ka'ba is in a filed, half-covered with a black veil. Alexander the Great, surrounded by eleven people, approaches it [12] (fig. 10).

During the first Safawid period, around 1505, a highly original painting of the Ka'ba in which Muhammad's ascension to heaven is represented above the Ka'ba, with its high door covered with a decorated black veil, was made in Tabuz, Persia, where the new Safawid dinasty had established itself. It is very refined and meticulous. Inside the holy precinct, with its greenish decorated floor, there are only one building and the pulpit. Several characters lean out above the main wall. The rectangular buildings surrounding the Ka'ba are also a big novelty, as is a landscape with palms and men. The sky is full of angels who accompany the Prophet [13] (fig. 11).

A miniature of Siyer-i-Nebi is dated 1595. It represents Muhammad teaching two Muslims how to pray around the Ka'ba, and is attacked by the pagan Gorashi Abujahl [14] (fig. 12).

A minitaure dating from the 16th century represents the ascension of Muhammad during the night, in which he is accompanied by angels, above the Ka'ba, that is surrounded by the buildings of Mecca. The holy precinct is hughly original and is seen from a bird's eye view [15] (fig. 13).

The Ka'ba was very represented in Egypt on glazed tiles, highly original in its composition and with a certain uniformity. One of the most original pieces is a tile dated 1676, in which the interior wall that surrounded the holy precinct is represented, with the lamps hanging in between the arches [16] (fig. 14).

A miniature by the Khaniza of Nizami represents Majnum praying in front of the Ka'ba. The miniature is very original in its composition. Only the Ka'ba is represented, covered with a decorated black veil, and the yellow door. Majnum, half naked, is praying accompanied by four people, two of them are also praying. Three buildings were drawn. The lamps are hanging at the back of the arches. The miniature is dated 1648 [17] (fig. 15).

Several very original and artistically refined and exquisite representations of the Ka'ba were made during the 17th century. Suffice to remember some of them, like therepresentations of the Ka'ba and of Medina in an Ottoman art Prayer Book [18] (fig. 16); the aerial view of the Ka'ba and its surrounding area, also of Ottoman art [19] (fig. 17); a blue Egyptian tile, with the Ka'ba and and the buildings around it, and the landscape of hills, a big novelty without close parallels [20] (fig. 18); the Ka'ba and Medina in En'a-i-Senif, which adds suras, verses and prayers from the Koran [21] (fig, 19); with ink, colours and gold on paper, copied in 1779 by Abdullah Edirnevu, natural of Edirne and calligraphy student with Sugli-Ahmed Dele, one of the best calligraphs in town and in Istanbul. From this century on, the representations of the Ka'ba and Medina are very numerous in prayer books. The same composition is repeated in the Prayer Handbook of Haili'l-Hayrat, copied in 1799 by Galatah Ahmed Naili, a follower of Sekerzale Mehmed Efendi of the school of Hafiz Ossnan and pupil of Mustafa Kütâli, one of the best calligraphists of the period. The compoition is also done in colours, on paper and with ink and gold [22] (fig. 20). Alongisde these works of art, one might add the splendid engravement made by Olson in 1790 of the Ka'ba, Mecca and the neighbouring landscape, which is very original [23] (fig. 21).

Other novelty and interesting representations of the Ka'ba include one dated 1315, in which the Prophet is in front of the Ka'ba door and its black cloth is held up by two companions. The Prophet holds the black stone on a carpet that is held up on its ends by two Muslims representing the four tribes. The composition has a fabolous colour and magnificent detail [24] (fig. 22). The carpet is a kilim from central Asia. The scene belongs to the Propht's life.

Also of great interest is the reprodcution of the Ka'ba seen from the interior, surrounded by famous buildings. It looks as if the mosque of Medina was reproduced in the lower right angle, possibly facing the Prophet's grave. The Ka'ba is surrounded by a double arcade [25] (fig. 23).

One last description of the Ka'ba that might be remembered, with a big novelty in the line of columns surrounding the holy place and Mecca's town planning [26] (fig. 24).

The representations of the Ka'ba do not follow a uniform model. The number of buildings inside the holy precinct is the same. Their distribution, the architecture of Mecca's buildings and the hill landscape varies somehow. Suffice to remember a few examples (figs. 25-28).

The Ka'ba in modern photograhpy

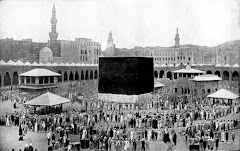

The Ka'ba started to be photographed since around 1880. These photographs are important to get to know the Ka'ba, its urban surroundings and the changes introduced (figs. 29-43) as time went by.

The Ka'ba and the prayer carpets

The Ka'ba and the Medina mosque are almost always represented in the prayer carpets on which Muslims pray on a daily basis in the direction of Mecca. It is popular art. Many of them have a high artistic standard. Colours are intense and decoration very diverse in its floral and geometric details.

Two identical prayer carpets can be found in Tripoli airport, they just change in colour. One is green and the other one red. The upper side only represents the Ka'ba (fig. 44).

A prayer carpet was sold in Tripoli's bazaar in February 2008 with the Ka'ba on a red background. The frame is decorated with flowers (fig. 45). The carpet headboard is frequently decorated with the Ka'ba and the Medina mosque.

Pilgrimage to the Ka'ba

It is one of the rules of Islamic religion that every Muslim has to fulfil at least once in a lifetime if possible. This subject repeats itself frequently in Muslim art.

In the book of Jalâl'àldin, Iksandar, dating from 1410-1411 and coming from Chiraz, the patio of the Ka'ba is represented full of pilgrims dressed in white. The Ka'ba is surrounded by the buildings of Mecca, as it frequently happens [27] (fig. 46).

The same religious scene can be found in a miniature, although it is probably not the pilgrimage to Mecca, since the building has white walls and is crowned by a dome. Pilgrims are distributed in two superimposed rows. They are dressed in white and have beards, according to order. On the inferior part, there are two males, one is sitting and the other kneeling below the triangular sunshades. They are also pilgrims, as they dressed in white [28] (fig. 47).

One last example that is convenient to remind, very original: the farewell of Abu Zayd and Al-Harith, who ride on camels to visit the Ka'ba and fulfill the mandatory pilgrimage [29] (fig. 48).

Muhammad and the Christian monks

The Prophet met with Christian monks. These important relationships have been captured in Muslim art. A miniature from Syria dating from the 15th century represents the meeting of young Muhammad with Christian monk Bahîrâ, who prophesied he would become a great prophet [30] (fig. 49).

An illustration in The Life of Muhammad by Siyer-i-Nebr shows the Prophet going to Christian monks in order to get his sight healed by them [31] (fig. 50). In an Ottoman miniature in this book, Muhammad is being served by Christian monks [32] (fig. 51).

In a copy of Translation of the Wonders of Creation around 1595, three Christian monks are talking with two Muslims in front of a Christian church and a classical Ottoman mosque [33] (fig. 52).

As well as with monk Bahîrâ, Muhammad met with other Christian monks. John of Damascus was born and lived many years in the Omeya court in Damascus. His father was a civil servant of Mu'âwiya I (661-680), of Yazid I (680-683) and Marwân I (684-685). Some Arab sources, the Arab bibliograhpy and Greek life made John of Damascus Prime Minister, Prime Counsellor, minister of the Governor, maybe with Abd-al-Malik (685-705) and Walid I (705-715), which qualified him to know Islam first hand during its early stage. John of Damascus (Book of Heresies I) collects an important information such as Muhammad surely visited an Arrian monk. The Prophet's belief that Jesus was only one man might be related to his teachings. Armenian text Against Muhammad, dated during the 10th-11th centuries, mentions a Monophysit monk, who were very numerous in Syria, who had contact with Muhammad. It is very likely that during the fifteen years he was engaged to Khadija, a rich merchant, he travelled for commercial reasons to Syria, where there were many monasteries. Nestorian Christology is pretty close to that of Islam. Muhammad might got to know about it first hand in Syria. It stressed the human nature of Jesus.

Christian monks are mentioned several times in the Koran. Sura 5.82 considers the Jews and their associates to be the most hostile towards the believers, and the Christians the most friendly one towards them. Priests and monks were amongst them, and they were not arrogant. Sura 9.31 states: "They have taken their doctors of law and their monks for lords besides Allah, and also the Messiah son of Maria and they were enjoined that they should serve one God only." This means that Christian monks had digressed from the original revelation. Sura 9.34 is against the monks: "Most surely many of the doctors of law and the monks eat away the property of men falsely, and turn them from Allah's way; and as for those who hoard up gold and silver and do not spend it in Allah's way, announce to them a painful chastisement." The doctors are Jews. Sura 57.27 reads: "Following them (Noah, Abraham and their descendants) we sent our other messengers, and we sent following their footsteps, Jesus, the son of Mary, and gave him the Gospel. We put tenderness and mercy in the heart of his followers." This was established by them, and would therefore be a divine institution. According to another version, monasticism would be a human invention. Nor Muhammad nor Jesus preached monasticism. The first Sura is in favour of Christian monks. An extracaconical, lately tradition states that Muhammad said that Islam had no monasticism.

D.J. Sahas, one of the best experts in John of Damascus [34], comments these Suras, correctly as we think [35]: "Even when the Qur'ân appears to be critical of monks, such a criticism is not directed towards ordinary individuals who have deviated from the submission to God alone and have talen rabbis and monks "as bords beside Allah". This criticism, however, is consistent with Islam's basic preoccupation with the unity and uniqueness of God (tawîd) and man's duty to be obedient to God alone. Indirectly this criticism constitutes an acknowledgement of the power of monasticism and of the influence monks were able to exercise upon the populace a power which, according to the Qur'ân, many monks have exploited. A similar kind of criticism is levelled against Christians in general who have exalted Jesus as God, although the Qur'ân is most respectful of Jesus himself. It is in this vein of thought that one must read what constitutes perhaps the most direct attack of the Qur'ân against monasticism where God is renouncing monasticism." D.J. Sahas follows the version that monasticism is a human invention: "But, again, in this passage monasticism is implicitly acknowledged as a way through which monks have chosen to please God through their devotion to Jesus. What is condemned here is the devotion to Jesus instead of a devotion to God alone. This is a late Medinan sûrah whose content and language reflect the growing disagreement of Islam with Christianity and its distance from the Christian community. Misguided monasticism is criticised because "many of the [Jewish] rabbis and the [Christian] monks devour the wealth of mankind wantonly and debar [men] from the way of Allah". One may want to note at this point the twofold characteristics of Islam, submission to God and charity as en expression of brotherhood and solidarity among all believers, which are also the characterisctics of monastic life. It is in faithfulness to these ideals and unter the light of and in response to misguided monasticism that one may want to see the modifications which Islam brought about to the otherwise ideal way of life (meaning, monasticism): opening up the life of submission (islam) to the community at large and making it a personal responsibility and a way of life for all, thus creating a "democracy of married monks"."

The strong influx of oriental monasticism has often been pointed out in the thinking of Muhammad and primitive Muslims [36]. D.J. Sahas considers regularity, punctuality and privacy of Muslim prayer during night and day, and the ritual that accompanies a Muslim's life (to wash before prayer, fasting, observation of holidays, circumcision, abstaining from wine and other practices that might be an expression of ritual life), to be an imitation or influence of monastic practice. Muhammad retired to a mountain and caves, as many oriental Christian ascetics. Angeology, prayer, alms and the idea of Final Judgement and hell, play a very important role in Islam and oriental monasticism. Constant prayer is the quintessence of monasticism, as it is for Muhammad and Muslims. Christian ascetics used epithets like "the Merciful", "the Compassionate" or "Creator" of the world in reference to God, just like Muhammad. Both religious groups were God fanatics and fought constantly against Paganism. The way Muslims prayed, rising, kneeling, touching the floor with the forehead and raising hands, is the same of oriental monks and of oriental Christianism. These same gestures live through among Chaldeans, Nestorians and Ethiopians.

John of Damascus forgot this important aspect to really understand the religiousness of Muhammad and that of Muslim religion, and the strong influx in oriental monasticism. D.J Sahas correctly titles Monastic Ethos and Spirituality and origins of Islam his documented research, and cathegoricaly states that ethos and monastic ideals are in the roots of Islam and are a part of its essential carachter, as recognized by Muslim specialist Seyed Husseyn Nasr, who writes: "It could be said that Islam is a democracy of married men, that is, a society in which equality exists in a religious sense, that all men are priests and equal to God, as his vicemanager on Earth." D.J. Sahas reminds that Monasticism was very frequent in the Syrian-Palestinian and Egyptian area during the 5th and 6th centuries. Arabic nomads knew well the ascetism of Monasticism, something which deeply impressed them, before and during the appearnce of Islam. Pre-islamic arabic poets often mention ascets in their daily life and thir ideals. Monastic literature, like the Narrations of Anastasius Sinaites (ca. 640-700), often refers to monks serving Arabs.

Sura 24.35 is as follows: Allah is the light of the heavens and the earth; a likeness of His light is as a niche in which is a lamp, the lamp is in a glass, (and) the glass is as it were a brightly shining star, lit from a blessed olive-tree, neither eastern nor western, the oil whereof almost gives light though fire touch it not-- light upon light-- Allah guides to His light whom He pleases, and Allah sets forth parables for men, and Allah is Cognizant of all things." It reminds of the light in the monks cell at night and in the desert, which had to be known by caravanners.

D.J. Sahas clarifies his thinking stating that not only light in the monks' cell, but his devoted life as an ascet, of prayer, of spirituality, of charity, the fear and hope before Judgement Day, are praised in these verses of Sura 24.36-38: "The lamps are in houses which Allah has permitted to be exalted and that His name may be remembered in them; there glorify Him therein in the mornings and the evenings. Men whom neither merchandise nor selling diverts from the remembrance of Allah and the keeping up of prayer and the giving of poor-rate; they fear a day in which the hearts and eyes shall turn about. That Allah may give them the best reward of what they have done, and give them more out of His grace; and Allah gives sustenance to whom He pleases without measure."

As this author indicates, these verses admire monastic life and the ideals that mean the

essential ethos of Islam: the way of life in the ideal of Muslim brothership, in which

prayer, prostration, regret, submission to God and responsability towards the social group are common and entwined. Charity and the ideals of monastic life was what christened Arabs [37] and influenced primitive Islam. The character of an ideal Arab at the time of Islam's appearance has been compared, probably, to that of a monk, as with the pre-islamic poet Zuhair.

Primitive oriental Christianism and Islam are linked to Monasticism, as seen in the lives of Saint Anthony, of Moschus (ca. 550-619) and Fileremos. D.J. Sahas maintains that in its whole and especially in primitive Islam, it is a product of the desert, in the widest sense of the word. Islam is linked to the ideals of Monasticism, with the exception of celibacy. Jesus never ordered celibacy, according to Paul (1 Cor. 7.25; 9.5). The Jewish world was unaware of chastity, witht the exception of a few ascetics like John the Baptist and the Esenians (Phil. Quod omnis probus liber, 12-13; Plin NH. V.17), but these, according to Josephus (BI. II.121) carried it out because they were persuaded that no woman is loyal to only one.

This strong influx of Monasticism in the though of Muhammad and of the first Muslims does not take away nothing of Koran's originality. The case is similar to that of Jesus, who was an apocalyptic.

Arab artsists who knew how to wonderfuly express a fundamental aspect of primitive Islam in their compositions.

Muhammad, Prophets of the Old Testament and Jesus

Muhammad was a great politician, who knew how to unite all Arabs, and a great man of God and religious genius. God entrusts Muhammad the Koran (55.1-2), which is the most pure expression of the most radical monotheism. A religion that has helped, throughout so many centuries, many millions of men and women to be profoundly religious, fair and charitable, and that has produced the pinnacle of human misticism, which is very similar to that of Christianism and has probably influenced it, can not be based on a false revelation. Christians can perfectly accept that Muhammad is a great profet and the last one after Jesus.

He linked his revelation to the main figures of the Old Testament and to Jesus. The revelation he received directly from God was the biblical revelation and that of Jesus. Jews and Christians had gotten of its course and He came sent by God to take it back to its primitive state. Balûrâ Waraqa Ibn Nawfal, a specialist in the Holy Bible and brother-in-law of the Profet's first wife, and in 615 the Ethiopians, who declared that their faith was not different than his, testified the authenticity of Muhammad's revelation.

Muslim artists have frequently used the most important characters of the Old Testament as a source of inspiration. Before Muhammad, the revelation was made to Abraham, Ismael, Isaac, Jacob and the tribes, Moses, Jesus and the prophets (2.136; 3.84; 19.58; 3.7), David (2.151); to Abraham, Ismael, Isaac, Jacob, the tribes, Jesus, Job, Jonas, Aaron and Salomon (4.163), and one must add Moses and Joseph (6.84). The Scriptures revealed before the Koran were the Tora and the Gospel (5.48.110). Other profets were Zacharias, John the Baptist, Elijah, Eliseus, Jonas and Lot (6.85-86).

Noe sailing round the Ka'ba in a ship has already been mentioned three times in this paper. An Ottoman manuscript dating at the end of the 16th ecentury represents Muhammad in the company of Moses and archangel Gabriel [38] (fig. 53). In a miniature in the History of Haziz-i-Abru, dated around 1425, Moses contemplates the Pharaoh's army drowning in the Red Sea [39] (fig. 54). A miniature of the school in Harar represents Muhammad's night journey above Burâo's cavalry, guided by archangel Gabriel, in front of the Baptist and Zachary [40] (fig. 55). The journey was made from the Ka'ba to the temple in Jerusalem. It took place in 620.

A painting by Aga Riza, dating from the years 1590-1600, in the book "History of the Prophets" by Nichapouri, represents Moses and Aaron [41] (fig. 56), who make a dragon appear in against the Pharaoh's magicians.

Still in the 19th century, Muslim artists represent characters of the Old Testament, like Moses presenting the bronze serpent [42] to the Jews in an Iranian miniature which decorates a Bible of the Hebrew community; Salomon [43] in an Iranian ceramic; or Joseph betrayed by his brothers in an Iranian tapestry from Keshan [44]. According to John of Damascus, Muhammad knew the Old Testament, which was widely used by Christian monks.

Muhammad had Jesus in high esteem. He considered him a great prophet (19.30), and as a prophet was he seen by his contemporaries (Lc. 7.16; Jn. 4.19; 9.17; Mt. 21.11), but not as a God. Neither Jesus nor Mary are of divine nature (5.17), because they were created (5.59). Because Jesus was not God, incarnation, redemption and Trinity are denied, just as defended by Gnostics and Docetists. Muhammad denies crucifixion and Jesus' death (4.157). For Muhammad, Jesus is the Anointed (3.45; 4.157, 171-172; 5.17.72.75; 9.30.31), sent by God (3.49), spirit of God and his word (4.171), God's servant (1.172). The Koran calls Jesus 23 times Son of Maria, a frequent expresion in non-canonic Christian books, as the Siriac Infancy Gospel (15 times), and the Arab Infancy Gospel (40 times), and one time in the canoninc Gospels (M.c. 6.3). This approximation of the Koran to non-canonic Gospels could be prove that Muhammad knew them well [45]. God gave Jesus clear proofs and he strenghtened him with the Holy Spirit (2.153).

This last evaluation of Jesus by Muhammad has been well reflected in Muslim art. Two examples should be enough: a miniature in Nizâmi's Khamza represents a miracle by Jesus [46] (fig. 57). The Koran exactly mentions Jesus's miracles. An Arab miniature of the 16th century clearly illustrates the importance of the two great prophets, Jesus and Muhammad, and their connection to Abraham. Muhammad and Jesus visit Abraham riding on a camel and a donkey [47] (fig. 58). The same scene repeats itself in a Persian miniature from the 17th century owed to Al-Biruni, with slight variations [48] (fig. 59). The Muslim artist wonderfully captures how Jesus and Muhammad start with Abraham's faith.

The Medina mosque

Ibn Yubayr [49] has left a good description of this sanctuary, as it was when he visited it:

The mosque served as a sanctuary and as housing for the Prophet. The rooms reserved for his women were preserved at the beginning of El-Ouahid's reign (705). An engraving of the 15th century represents the Medina mosque and the Prophet's tomb. It allows to have an exact idea of its construction [50] (fig. 60). An engraving dated in the 18th century is a good representation of the mosque [51] (fig. 61). It is inspired by an ancient model.

The construction is represented in a miniature of the 18th century [52] (fig. 62), or the Prophet preaching about the mosque, the disposition of the mosque and the tomb in a popular miniature of Iraq [53] (fig. 63). Muhammad built the first mosque of the Muslim world after he fled from Mecca in 622. A painting in the manuscript of Siyer-Nebî from the late 16th century represents this construction [54] (fig. 64). A 1790 lithography excellently represented the town of Medina, fortified, with the mosque in the middle of the city [55] (fig. 65). The Prophet is represented preaching in the Medina mosque [56] (fig. 66) in an Ottoman miniature dating from the 15th century, or in another Ottoman miniature from the 14the century, in which Muhammad preaches to the faithful [57] (fig. 67).

The representation of the Medina mosque with the Prophet's tomb in the Koran of Ottoman Sultan Usman III is very original. It is nowadays in the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum in Istambul [58] (fig. 68). An excellent image of the Medina mosque in lively colours was reproduced in a prayer book from the 18th century [59] (fig. 69).

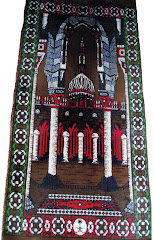

Representations of the Medina Mosque in prayer carpets

The Medina Mosque, on its own or in the company of the Ka'ba, frequently decorates prayer carpets. The Mosque occupies the carpet's head. Some specific details vary a lot from one piece to another. In some the arches of the inner Holy precinct are present. The rim and interior have geometric and floral motifs, which offer great elegance to the whole. There are also colour combinations on each carpet, very lively and well achieved [60] (figs. 70-81).

It is very frequent that the same carpet represents the two most respected by Muslims, both visited by Muhammad (figs. 82-85).

Several other representations of the Ka'ba

Besides the mentioned representations of the Ka'ba, several other might be recalled before finishing this study, such as that of Abraham building the Ka'ba [61] (fig. 86), the Ka'ba of Muhyi Lari, Futuh al-haramayn, dated around 1540 [62] (fig. 87), and the Ottoman symbolic image of the Ka'ba [63] (fig. 88).